Something horrible is happening in Atlanta. A much needed public forest, originally in 2017 planned to exist undeveloped as the “lungs” of the city, is under attack. It has been systematically invaded by combined police forces intent on building a $90 million training and “morale” facility, after the Atlanta City Council voted to allow a nonprofit called the Atlanta Police Foundation to build the facility (albeit with $30 million of the costs coming from Atlanta taxpayers.) Would it surprise you to hear that this beautiful green space is surrounded by working class and poor communities, predominantly black, historically segregated, environmentally and economically disadvantaged?

The broad outlines of the backstory on the struggle from an apolitical point of view can be garnered from CNN:

[The City of] Atlanta and then-Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms were in the national spotlight in 2020 as protests erupted across the country over police killings of Black people, including Rayshard Brooks, a Black man fatally shot in the back by Atlanta police… The city’s police chief resigned and Bottoms denounced the “chaos” she said was unfolding on the city’s streets, adding she was trying to strike a “tough balance” between criticizing police officers and supporting the ones who protected the city.In the spring of 2021, following mounting pressure over a demoralized police force, Bottoms announced plans to build a new police training academy in an unincorporated part of neighboring DeKalb County on a controversial parcel of land owned and used as a prison farm by the city for much of the 1900s, sprawling across more than 300 acres… “We knew that (the training facility) was a direct response to the uprisings that took place in 2020,” said Kwame Olufemi, of Community Movement Builders, a Black member-based grassroots organization opposing the project…

(I)n September 2021, after hearing roughly 17 hours of public comment – the majority of which was against the training center – the Atlanta City Council approved a ground lease agreement with the Atlanta Police Foundation, allowing for 85 acres of the prison farm site to be turned into the training facility while the other 265 is slated to be preserved as greenspace. Andre Dickens, Atlanta’s current mayor, was among the council members who voted for the lease. “Everybody was floored,” said Jacqueline Echols, board president for the South River Watershed Alliance, an organization working to protect the river. “Just in 2017 they’d said this would be a park and a community investment.”

The above quoted article makes light mention of “activists” known to be camping in the forest, but doesn’t go into much detail or seem to consider them an important factor. It was about this time that the activist community began referring to the impending project as “Cop City” and calling the tract of forest with its ruined old prison farm and endangered South River, by its Muscogee name – Weelaunee. Other names used in the media include the South River Forest, the Atlanta Forest, and Intrenchment Creek Park for a section of it adjacent to the old Prison Farm ruins, which the cops plan to bulldoze for their building site.

A more human and humane story contemporary with this one was found on an excellent regional blog called The Bitter Southerner, in a December 13, 2022 piece by David Peisner called “The Forest for the Trees.” (The article is lavishly illustrated by photographs from Fernando Decillis, and so I strongly recommend you click through and read the whole thing, or at least look at the pictures.)

Peisner went to the forest and talked to the occupiers themselves. It’s a very human-level story, made especially poignant if you know one of these people will be dead in a little over a month. He starts with a deep dive into the Prison Farm part of the history of this place, a heartrending tale in its own right. Then he lines up the recent history, the funders of the Atlanta Police Foundation, the mainstream community activists and neighborhood associations on the “No Cop City” side, and the same tale that CNN told, drily, about the city government’s disappointing actions, about which he says:

Coming on the heels of the nationwide Black Lives Matter protests following the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police, and accompanying local protests that were inflamed by the subsequent shooting death of Rayshard Brooks by Atlanta police, the decision to build the training facility on this land looks to be, at the very least, an extraordinary misreading of the room. Amid calls to defund the police, the city was committing at least $90 million — one-third from taxpayers — to its police force, whose morale was reportedly low following the previous year’s protests.

Here’s an excerpt from the blog where he is talking to a Forest Defender he calls Tortuguita, a person he later admitted he spent more time with than most other sources because they were just such a delightful and interesting person.

“Within the movement, there’s this constant struggle to avoid concentration of power, to disseminate decision-making,” a forest defender who goes by Tortuguita told me. “It’s harder to do anything because people are accustomed to following orders and having strict hierarchies. It gets tricky when you need to do something quickly, but everything kind of works out”… The decision to organize the movement this way is strategic. If nobody’s in charge, nobody can negotiate away demands. In fact, nobody can negotiate at all. “There’s no way to co-opt it,” said Tortuguita. It’s unreasonable by design… “It’s incredibly important to continue having popular support,” said Tortuguita, who uses they/them pronouns. “Cop City is incredibly unpopular already. We’re very popular. We’re cool.” They laughed as they said that last bit, but, without a doubt, the movement has succeeded in painting the forest defenders as a scrappy, idealistic David battling a heartless, moneyed Goliath. “We get a lot of support from people who live here, and that’s important because we win through nonviolence. We’re not going to beat them at violence. But we can beat them in public opinion, in the courts even.”

Fast forward to January 2023 and the Atlanta Police Department (APD) (and its companions in crime, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI), the DeKalb County Sheriff Department, and the Georgia State Patrol) started playing real hardball. They started forcibly evicting Forest Defenders, and charging them with felony offenses, mostly “domestic terrorism.” And then, on January 18, someone died. Tortuguita. The police claimed that they shot at them, but the total opacity of news coming from police sources makes this seem unlikely.

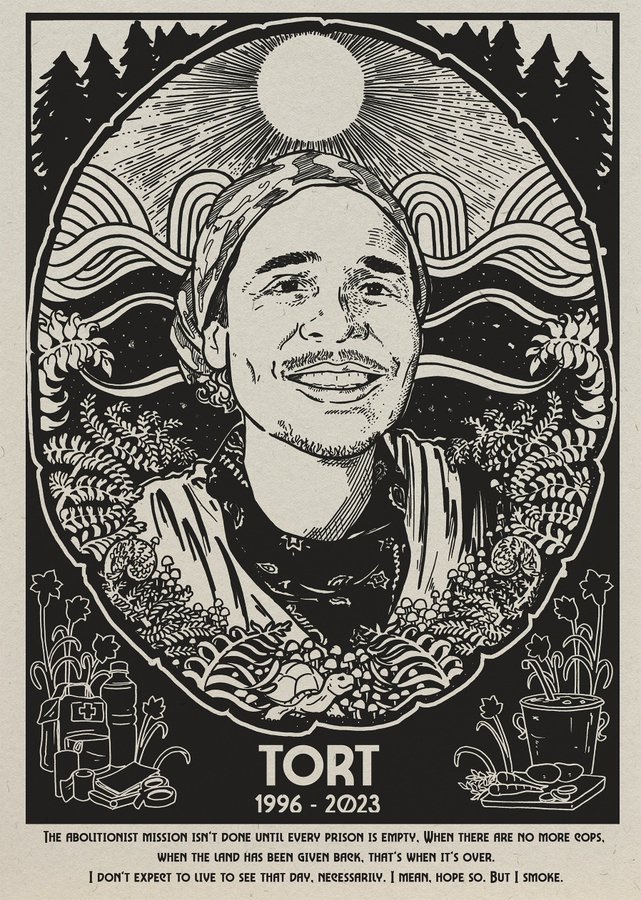

Peisner went back to the forest a few days later and wrote “Little Turtle’s War,” catching up on the escalation in late December and into 2023, and focusing on Tortuguita’s murder. He had pages of quotes from Tortuguita that had not made it into his first article. One of them has become the iconic tribute to Little Turtle, who has been revealed as Manuel Esteban Paez Terán.

“The abolitionist mission isn’t done until every prison is empty,” Teran told me. “When there are no more cops, when the land has been given back, that’s when it’s over.” I must’ve shaken my head a little at the grandiosity of this statement because Teran immediately broke into a sheepish smile. “I don’t expect to live to see that day, necessarily. I mean, hope so. But I smoke.”

It is very apparent that the police are lying. Of course, they do that a lot, but are usually not so barefaced and unconvincing. Coverage in the “mainstream media” is sparse and noncommittal, simply repeating police statements and not even mentioning that these accounts conflict with both reality and each other. (One notable exception is the US edition of The Guardian, which published “Assassinated in cold blood: activist killed protesting Georgia’s ‘Cop City.’”) Considering that the defense of the forest attracted activists from across the US and even worldwide, and that a majority of Atlanta citizens were opposed to Cop City, coverage before January 18, 2023 portraying it as a niche issue was odd, often dismissing the opposition as “controversy.” But on that day, some unnamed cop committed a murder that ought to be as awakening and transformative as that of George Floyd. Still the best inkling of what’s going on comes from blogs, indy media, or reading between the lines of CNN’s curiously flat reporting from its supposed beloved hometown.

Another quotable outtake from Peisner’s December blog post kind of sums up why this is happening here in Atlanta. Also it’s the best explanation of the unique thing (not in a nice way) that Atlanta just is, a factor that drove me away from my former hometown 39 years ago:

Atlanta’s favorite story about itself is that it’s “the city too busy to hate.” The phrase, which emerged in the late 1950s and early 1960s, is often invoked to explain how the city became a cradle of the Civil Rights Movement, but it’s code for a darker truth: Money trumps everything here. Sure, that’s true everywhere, I suppose, but few places stamp it on their tourist brochure like a badge of honor. Nothing stands in the way of economic progress here. Property developers run this city.

By Deb K R